In October 2014, architects Dong-Ping Wong and Oana Stanescu held their first fall benefit in support of their floating swimming pool project, + POOL, at Jane’s Carousel in Brooklyn Bridge Park in New York. Located between the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges, it's also where, in 2010, Wong and Stanescu made initial renderings of the plus sign-shaped pool that filters water from and floats on top of the East River in New York City. Originally announced via Kickstarter crowdfunding in 2011, through renderings, the first-of-its-kind + POOL instantly went viral and had garnered an array of fans. Kanye West, Olympic swimmer Connor Dwyer, Carol Lim and Humberto Leon of Opening Ceremony, and Karen Wong of the New Museum were just some of the big names who attended this first celebration of the project.

A carousel may be an odd place to host a fundraising gala, but not for Wong and Stanescu, who are masters in combining the unexpected—a children’s carousel with well-dressed adults, in this case—and creating memorable spaces. “The gala was the first time that all of the various people we had been talking to came together, in one place,” says Stanescu, who speaks quickly and assertively. At 34 years old, she is charismatic in both her directness and warmth, yet is often found wearing dark colors that complement her wavy, black hair. “There were scientists, professors, politicians, artists, museum directors, cool kids, models, and teachers. The diversity of backgrounds was mind-blowing.”

Since establishing their architecture studio, Family New York, seven years ago, Wong and Stanescu have been bridging the gap between the less accessible design world and mainstream culture. + POOL and its viral, Internet-driven, crowd-sourced reception was early evidence of this. Their work on Kanye West’s Yeezus tour stage in 2013—an enormous, moveable mountain—spread just as far, beyond the entertainment realm, through social media. They have embraced a multidisciplinary approach that is intentionally fun and focused on the emotionally impactful aspects of buildings, homes, and space in general.

But Wong and Stanescu aren’t aiming to create “popular” work. At the core of their existence as individuals, and as a unified studio, is a desire to use architecture to efficiently improve people’s lives and provide essential resources. They are at the forefront of productive architecture, a term they coined, and that Wong presented at a 2013 TED Talk, based on fulfilling human needs beyond housing: clean water, air, and food, among them. It exists in direct opposition to the ubiquity of expensive, pre-Great Recession buildings, erected in the early 2000s in cities like Dubai and Doha, that were seen as gratuitously tall and opulent, as if only to display grandiosity. Wong and Stanescu’s practice, and early projects, starkly contrast this arguably wasteful style of design.

“The ideas we have in productive architecture, and the intention of making things sustainable, and simply better for people, really comes from our inner selves—who we are as people,” says Stanescu. “It comes from how we grew up and how we see the world.”

Wong and Stanescu had vastly different upbringings. Wong, who is 37 years old, wears wire-frame glasses and is often dressed in button-up shirts. He is from sunny San Diego, where he surfed in his free time. Stanescu grew up hiking and skiing in formerly communist Romania, during and after the Romanian Revolution. Neither were heavily exposed to the arts or architecture before their teenage years.

Wong discovered architecture at a two-week summer arts camp his parents forced him to attend during high school. A few years later, he realized he wanted to be an architect after house hunting with his parents, who were looking for a tract home in a suburban San Diego development. Out of four cookie-cutter options, Wong noticed a bridge between two bedrooms on the second floor of one house. “This is what architecture is,” he recalls thinking. “You design those differences, and they have a huge impact on how you feel about space.”

He was further exposed to purpose-driven design at UC Berkeley, where he received his undergraduate architecture degree, through one of his professors, Richard Whitaker, who is known for designing part of the Sea Ranch, a utopian, coastal residential project developed in the ‘60s. "At the top of every stair, you need to have a little seat,” Whitaker told Wong’s class. “Because that's where the grandfather has to sit down, to be able to take a rest, but also to read a story to his grandkids."

Stanescu’s experience at the Polytechnic University of Timișoara, in Western Romania’s cultural capital, was similarly eye-opening. “It was the first time I began to understand architecture,” she says. “From an intellectual point of view, it was mind-blowing. I started studying art history. It was an explosion of information.”

In an effort to expand her education beyond Romania, Stanescu applied for, and was granted, a two-year, double-graduate, full-ride scholarship to the Polytechnic University of Milan. A week before leaving, with bags packed, the Italian consulate informed her that her visa had been denied. “It was a huge letdown for me,” she says. “But I couldn’t dwell on it. I ended up going to Seville, Spain on another scholarship.”

It was in Spain that Stanescu saw a poster for a student position at OMA New York, a prestigious, award-winning firm in New York City that would later be renamed to REX Architecture. She applied for the internship, and then deleted the email from her sent folder, anticipating a rejection. This time she had better luck; she got both the job at REX and the visa.

“Growing up in Romania, at the cusp of Communism collapsing, I saw everything crumble when I was little,” explains Stanescu. “In a way, those situations can yield change and growth. This is partly the reason why I see the world, and the world of architecture, as constant sources of possibilities.”

In 2005, Wong and Stanescu met at REX. Wong was a junior associate and had just finished his Master’s degree at Columbia University, while Stanescu was an intern. “Our bosses identified that we had a good partnership well before we did,” says Wong. Their first project was Kentucky’s Louisville Museum Plaza, a mixed-use, 62-story building—a combination of museum, commercial space, residential dwellings, hotel, and retail. Though it was never built, due to funding lost during the recession, it was a foundational, formative project for Wong and Stanescu. “By the time we both left REX, it was pretty clear that we hoped to continue working together, even though we didn’t formalize it right away,” says Wong.

“We were so in sync,” Stanescu adds. “We were finishing each other's sentences. We were communicating ideas with each other really quickly. We were working too fast. People couldn’t catch up with us.”

After a one-year stint at REX, Stanescu began a series of architecture jobs around the world, which she calls her “second education,” including with the SANAA firm in Tokyo, Architecture for Humanity in South Africa, photographer Iwan Baan in various countries in Africa, and architects Herzog and de Meuron in Basel, Switzerland, before eventually returning to New York to work at the firm, OMA.

Wong also left REX, six months before the recession hit, and began freelancing from New York. He would email Stanescu, asking her to review his work through submissions to a private blog on the now-antiquated Blogger platform. In 2009, they officially began working together on various projects, including a sustainable housing block in Dallas and a contemporary art museum and circular pedestrian bridge in Slovenia. Many of these early projects were competitions—an opportunity to design freely around a loose brief—done completely via the Internet, on different time zones, and by using blog posts to pitch ideas, provide feedback, and share materials. The process was ahead of its time, years before the dawn of today’s online collaboration tools that greatly simplify this kind of cross-functional work.

“I remember distinctly that, at one point, I was in South Africa, Dong was in New York, and Erez, our first boss who we still worked with, had moved to Tel Aviv,” Stanescu says. “We were working on a competition together, and I couldn't help but think that it was easier to work with them on different continents, in different time zones, than with people in the same room who don’t understand you in the same natural way.”

Both Wong and Stanescu attribute their early freelance collaborations, as well as the values they would eventually champion as a firm, to the effects of the recession. “When we decided to formally start Family New York in 2010, it wasn’t like we were giving up any great full-time job offers, because there weren't any,” says Wong. “Before the recession, we saw insane money going into projects that looked impressive but were, in our opinion, pretty useless. We thought, ‘If we’re ever going to ask people for their money, or dedicate our time to something, it needs to be substantially worthwhile.’”

+ POOL was the first project Wong and Stanescu officially announced, and began fundraising for, as Family New York. Their friends at PlayLab, a New York-based creative studio, were essential to establishing the non-profit and educational aspects of the project from early on. As soon as they put it on Kickstarter, on June 15, 2011, there was an unexpected outpouring of support and press praising the pool’s communal purpose and innovative, buoyant, plus sign-shaped design. The + POOL will clean water from the Hudson River through a filtration system in its walls. It also serves multiple kinds of swimmers through four distinct arms: a Children's Pool, a Sports Pool, a Lap Pool, and a Lounge Pool. By combining one or more sections, the pool can turn into an Olympic-length lap pool or a completely open, 9,000-square-foot pool for play.

After raising $41,647 in the summer of 2011—surpassing their initial $25,000 goal—Family New York and PlayLab began offering customizable tiles in the summer of 2013, raising $273,114 more. Since then, they have been working to raise a total of $21 million to cover water filtration development, planning, building, and maintenance costs.

Their water filtration research, in partnership with engineering firm Arup, has yielded some of the most detailed water quality data the city has ever had, and is inventing a new, potentially transferable model for cities beyond New York and applications beyond pools.

“+ POOL showed us the potential of design,” says Stanescu. “Meaning that people literally just looked at the image and thought, ‘I want this to happen. I'm going to put my money towards it.’”

They also attribute the launch of + POOL, slated to be built and open to the public by summer 2021, to their blind ambition. “We had no reputation, no staff, no money,” says Wong. “We just decided to put it on Kickstarter to see what would happen.” + POOL is scheduled to be completed in four years, but ongoing maintenance is needed to keep it going after it opens. “The goal is that it’s not only environmentally sustainable but also economically sustainable,” says Wong.“There are no codes or regulatory laws written for a project like this, so even if we had wanted to finish it within five years, or by 2016, it just wasn’t possible.”

Wong and Stanescu have deliberately turned down funding from luxury developers, with the aim of keeping the project democratic—funded by the people, for the people. In addition to fundraising events, they also partnered with PlayLab to start an educational swim school that offers kids free swimming lessons. The gesture harkens back to Wong and Stanescu’s humanitarian values, as well as their own childhood activities—Stanescu swimming in lakes and Wong surfing.

Part of + POOL’s statement was communicated through an intentionally untraditional design, the plus sign. “We knew that the Plus was going to look funny,” clarifies Wong. “But that was actually very important. It had to look different from a normal pool to be an entry point into the project and hold people’s attention.”

Stanescu echoes and broadens the sentiment: “We want the work to stand for something. Architecture is political at the end of the day. You’re changing cities, affecting the way people live, altering what they see when they walk down the street. Each project makes a public statement and will be remembered in some way.”

Not long after the launch of + POOL, in April 2013, Stanescu got a call from Kanye West, who asked if she could fly to Paris. West needed help to re-designing his apartment there.

Stanescu and West first met in the spring of 2012. Working at OMA, the last firm she joined before doing Family full-time, Stanescu was instrumental in the development of West’s seven-screen audio-visual experience, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2012 and was later patented by West. Only those at the Cannes debut witnessed the project; it hasn’t been shown publicly since.

“As an architect, it’s very rare that you work with clients who completely understand all dimensions of a project,” Stanescu says of West. “Kanye works at such a high level, and he helps every project go further. Not only does he learn from us, but we learn from him.”

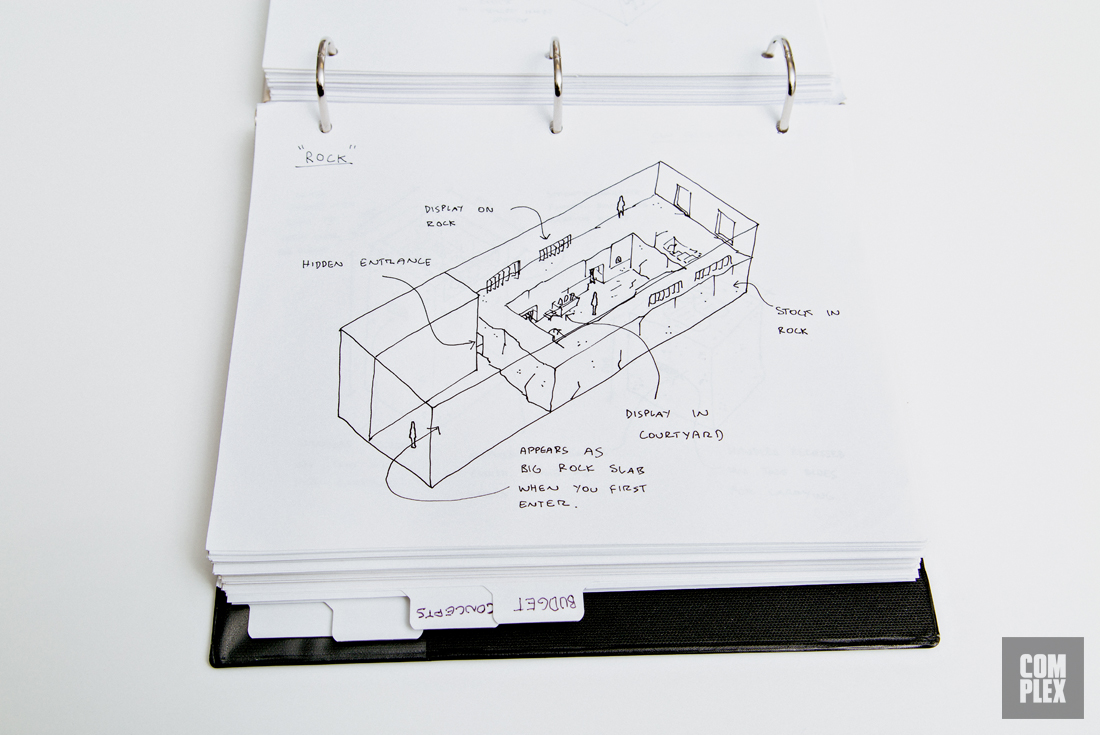

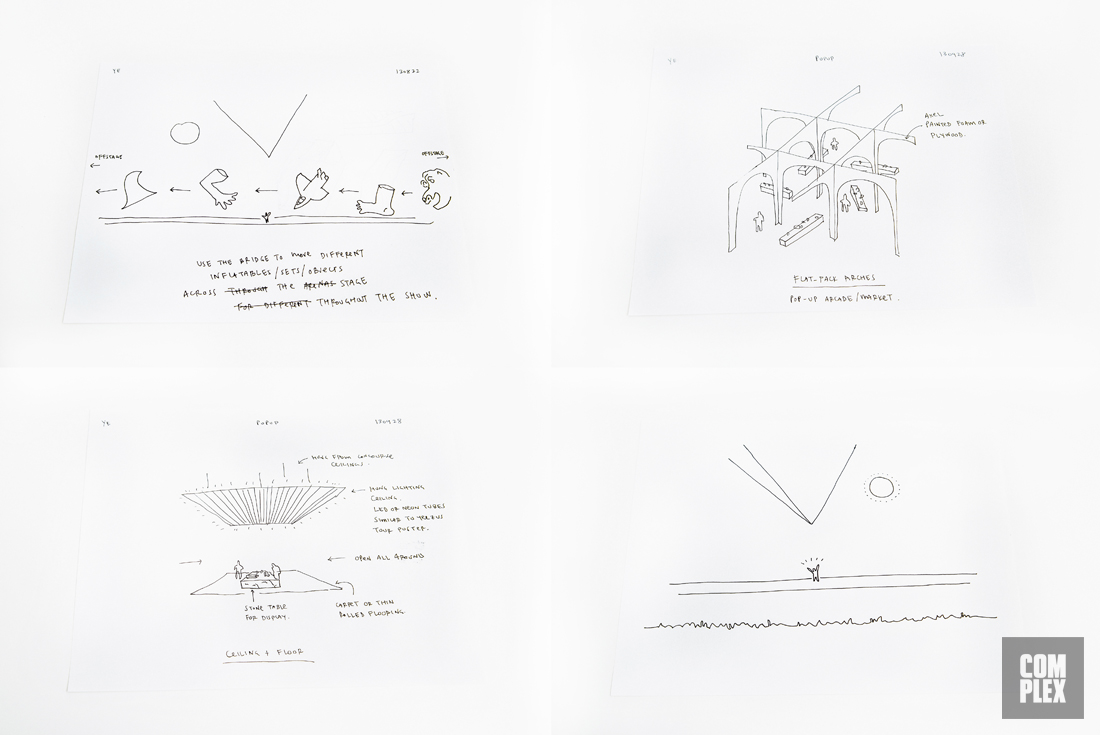

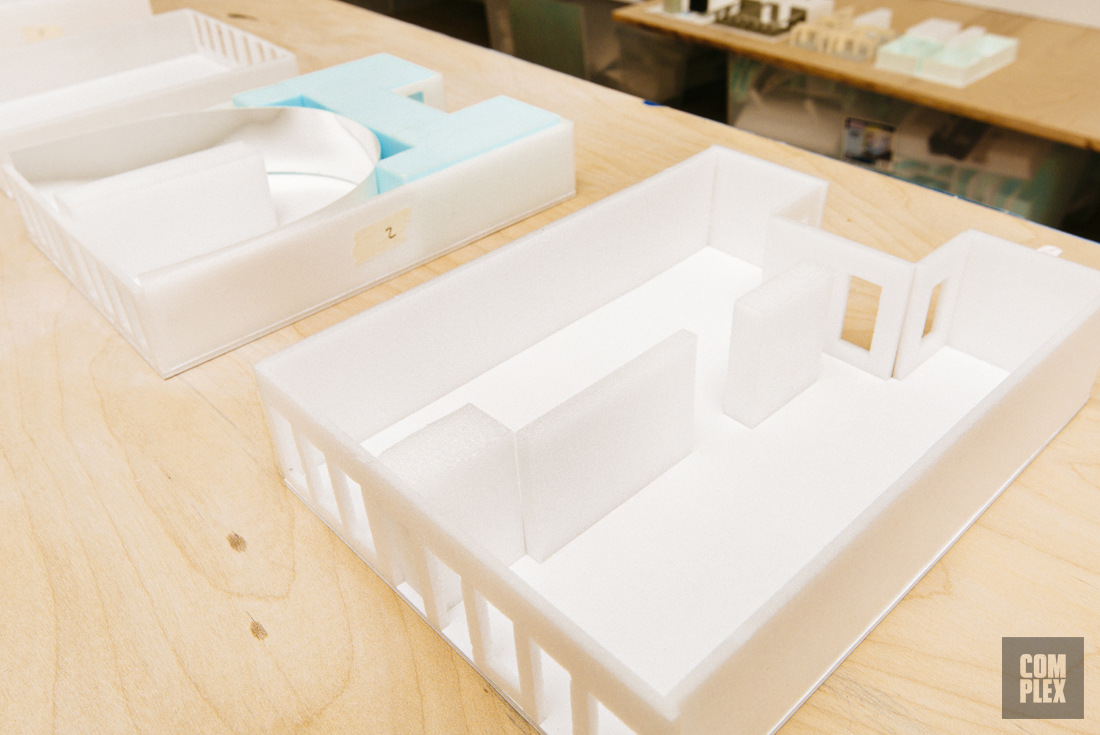

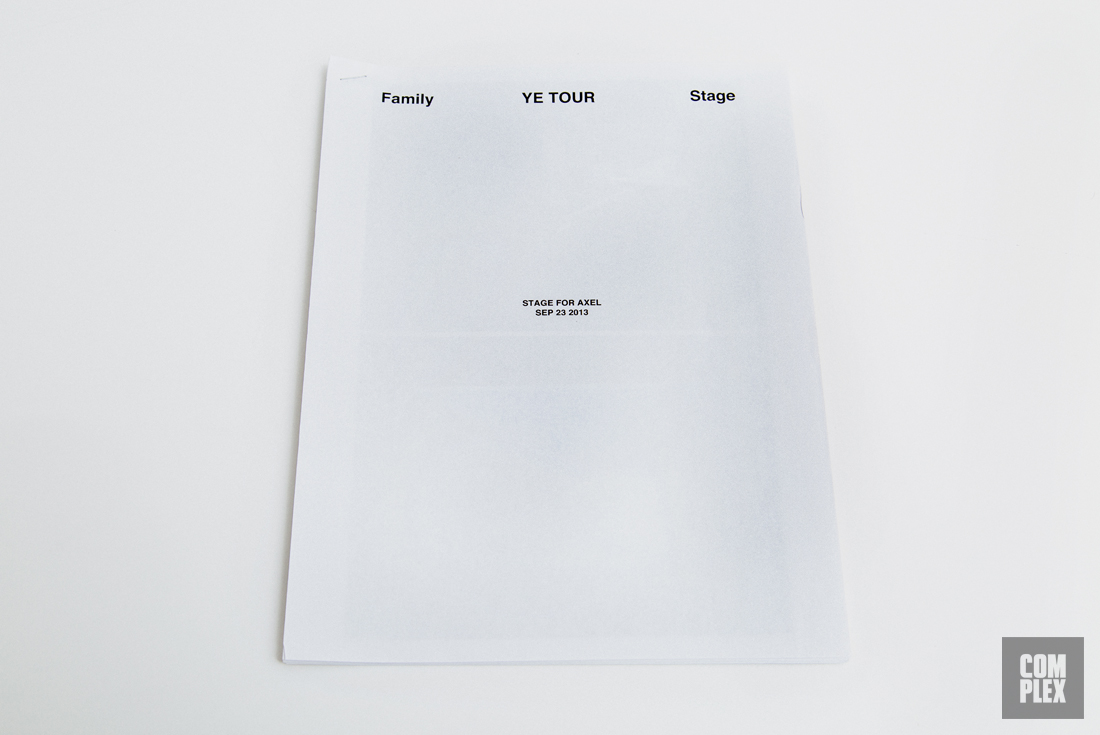

Not knowing she’d ever work with West again, Stanescu surprised Wong on his birthday with concert tickets to West and Jay Z’s 2012 Watch The Throne concert. She deceptively asked him to meet her near Madison Square Garden for a talk by architect Rem Koolhaas. Wong and Stanescu found themselves enthralled by Watch the Throne’s ambitious stage design, where West and Jay Z stood on gigantic cubes covered in LED screens. At the time, they didn’t know they’d eventually witness the creation of West’s next solo album, 2013’s Yeezus, and help design the Yeezus tour’s iconic mountain stage.

“When we were working on his houses in Paris and Los Angeles, Kanye would be running around, talking about his clothing line with another group in the room,” Wong says. “Then he’d shift to another group to talk about finalizing the Yeezus album while making last-minute edits and changing tracks. Then he’d come back to us and be like, ‘What if we did this?’”

At times, the environment was so intense that Wong and Stanescu took shifts. “With most clients, you meet, you think of some ideas, and you come back in a week or two weeks to present,” says Wong. “It's relatively organized. With Kanye, it's very much like, ‘Come. We're going to work with you nonstop for a week. Let’s get this done tomorrow.’”

A few of the projects they worked on, which they decline to discuss, are described vaguely as, “a ton of stuff that Kanye just has interest in trying to push.”

Very quickly, Wong and Stanescu found themselves in admiration of West’s multidisciplinary, fast-paced, highly involved and collaborative creative process. “Working with him helped me to understand that, basically, all creative fields deal with similar concepts,” says Stanescu. “They all necessitate a process of editing, testing, and changing over and over again.”

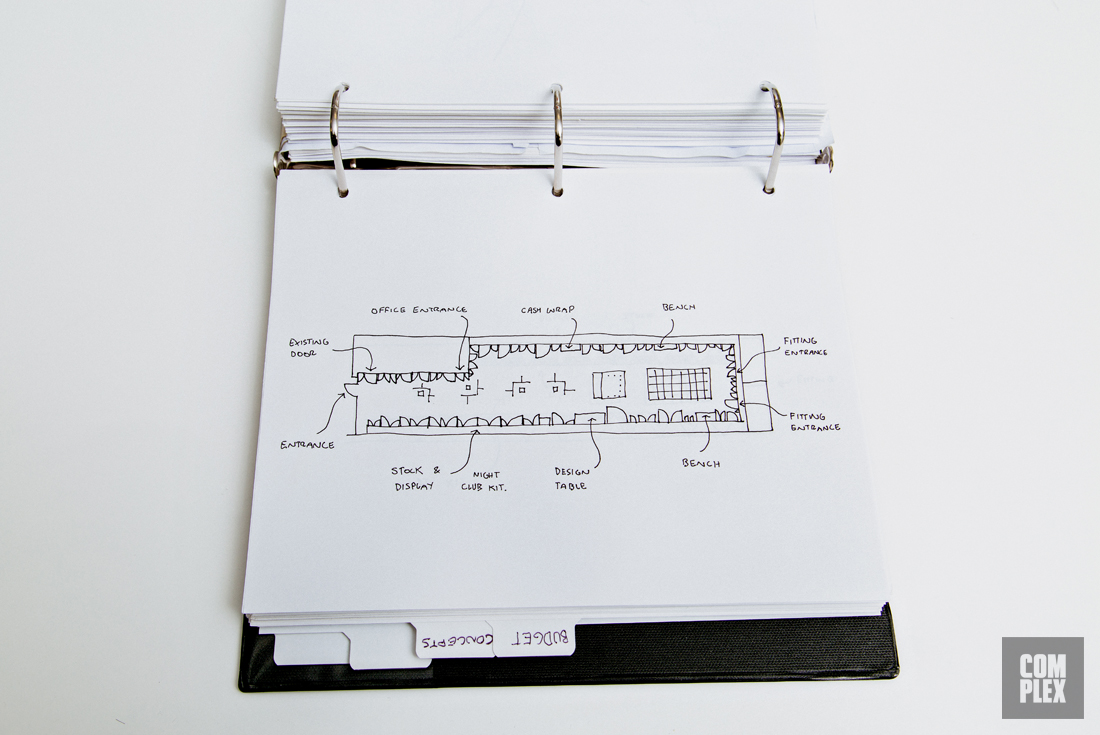

Through West, they met Virgil Abloh, the rapper’s longtime creative director. Abloh, who was trained as an architect and is a fan of Family New York’s work, was about to open a flagship store for his label Off-White in Hong Kong. On the way to West’s wedding in Florence in 2014, he asked Wong and Stanescu if they would collaborate on the shop, Family New York’s first retail project.

After accepting the project on the spot, work on Off-White Hong Kong was done purely by text message. The three of them developed a concept that would translate to stores in Singapore, Tokyo, Shanghai, Beijing, Toronto, New York, and a second shop in Hong Kong. “Let’s find another way to bring people in,” Wong recalls discussing with Abloh. “Let’s just make a good place to hang out, a place you want to be, like a calm, relaxed garden courtyard without product up in your face.”

Wong and Stanescu didn’t see Abloh again until the day of the Off-White Hong Kong store’s opening in 2015. “We would sketch stuff or make renderings and then scan or photograph them so we could text him,” Wong remembers. “I think he worked on the store completely on his phone. He responded really quickly and would understand sketches in the same way that we understand them. We still have this text thread between him and the office, and we just post random ideas as they come.”

Stanescu articulates Family’s shared sensibility with Abloh as one of making the design process, and the process of becoming a designer, more accessible. “Part of what I’ve loved about working with Virgil on these stores is that the clothes aren’t the priority,” she says. “Whether it's fashion or music, or a collaboration with IKEA, they are almost just excuses—excuses to reach young people, if that makes sense. He’s trying to tell them that they can do this, too.”

“I love when our different worlds collide. There’s a range of what you can do with architecture, who you can do it for, and the way in which it’s done.”

Earlier this year, Stanescu was diagnosed with lung cancer and spent the last few months out of the office having surgery and, thankfully, fully recovering. Wong took over running the studio, at a time when more clients were approaching them than ever before. “I can’t imagine what it means to go through this without someone to shield you from the stress and keep things going,” says Stanescu. “Dong has been immensely helpful in allowing me to not only recover but process the whole thing.”

During Stanescu’s time off, Wong focused on continual + POOL work, a store/office for A-Trak’s Fool’s Gold Records, teaching courses at Columbia, and a new project called High Court, a members-only health, fitness, and social space opening later this year in downtown Manhattan. High Court, in particular, partially speaks to the direction Wong would like to continue to take Family’s projects.

“I have a big interest in working on public spaces that you often forget about in cities,” says Wong. “Projects like public libraries or recreation centers that are purely for the community are usually not very interesting architecturally. Philosophically, they have an incredible use; they are places for the public to go and be engaged in their communities. I think that's becoming more and more important.”

This persistent generosity, grounded in a desire to continually improve the lives of others, is characterized by Stanescu as her understanding of the American dream. “In my mind, the American dream comes with responsibility,” she says. “You should aim high and have really audacious plans. There are so many possibilities, so you might as well explore them. This is an audacity that both Dong and I enjoy.”

Family’s work has so far been executed with this fearless, optimistic ambition. It’s the kind that comes from being self-realized, from understanding what the highest human highs feel like, as well as the lowest lows—the fall of Communism and the rebuilding of a society afterward, the crash of the recession and the productive architecture movement in its wake, the diagnosis of cancer and subsequently beating it, or simply drying off after a good, long swim.

“I love when our different worlds collide,” Stanescu says. “There’s a range of what you can do with architecture, who you can do it for, and the way in which it’s done. It’s immense.”