Rap fans—and even artists like Rick Ross—have been captivated by the nearly three-year saga of Lil Wayne feuding with Birdman and Cash Money Records. The battle (with occasional hints towards reconciliation) has raged both in the courtroom and in the court of public opinion, with both sides pleading their cases on socialmedia and onstage.

Wayne, who has been recording with Cash Money Records since he was 12 years old, accused label co-founder Bryan Williams, alternately known as “Birdman” and “Baby,” of stealing over 50 million dollars from him. Birdman and Weezy had been so close that Wayne constantly referred to the elder man as his father. The two even titled their 2006 duet album Like Father, Like Son, so the news of the alleged shady business practices caught many by surprise.

But perhaps it shouldn’t have. There has been a long history of accusations of nonpayment, underpayment, and various other bad business practices leveled at Birdman. Tyga, former in-house producer Mannie Fresh, “A Milli” producer Bangladesh, and Hot Boys member B.G. are only some of the people who have complained about Birdman and his brother and co-founder, Ronald “Slim” Williams, over the years.

In fact, according to some of the people who were there at the beginning, Cash Money has always been shady about its cash money. Even when it was a regional label, from its founding in 1991 until a team-up with Universal Records in 1998, tales abound of Birdman and Slim ripping off young artists. The entire roster (at least those who survived—a number were killed during a particularly violent era in New Orleans), minus a teenage Wayne and B.G., left the label prior to the Universal deal, citing almost identical complaints about missing dough.

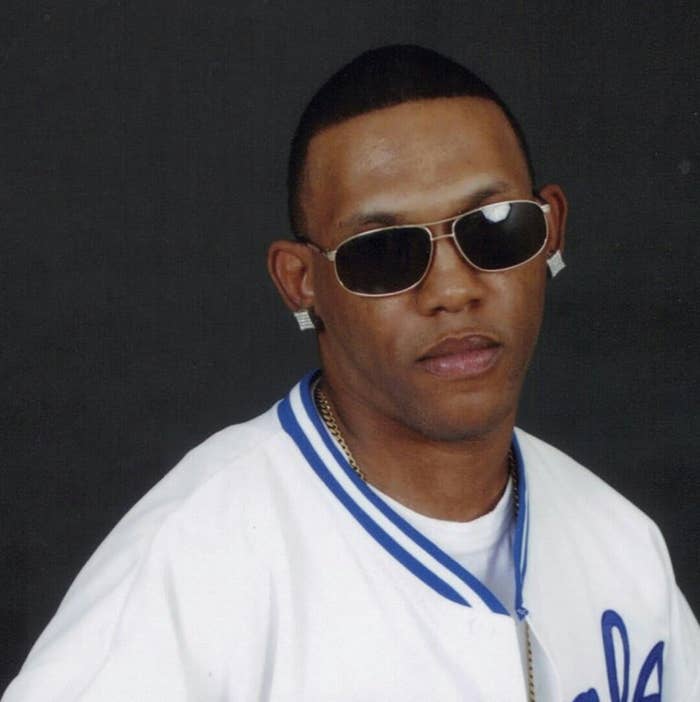

Lil Slim, who recorded three albums for Cash Money between 1993 and 1995, was signed fresh out of high school at 18.

“I was really young when I went into it. All of us was young,” he tells me from California when I reach him over the phone. “Most of us was between 18 and 20.”

And some were even younger. Trishell Williams, who raps and sings under the name Ms. Tee, was just 14 when she got involved with Cash Money.

She had some ideas about why the label worked with teenagers. “I think Cash Money signed young people because they don’t really know business,” she told DJ Booth. “If you don’t know the business you not gonna ask that many questions.”

Right from the beginning, Baby would preach that the label was a “family”—and would frequently use that very idea to shut down any questioning of his methods. One of his most common tricks, rappers of that era consistently say, was using his position as both label head and manager of all the artists to deceive them about concert fees.

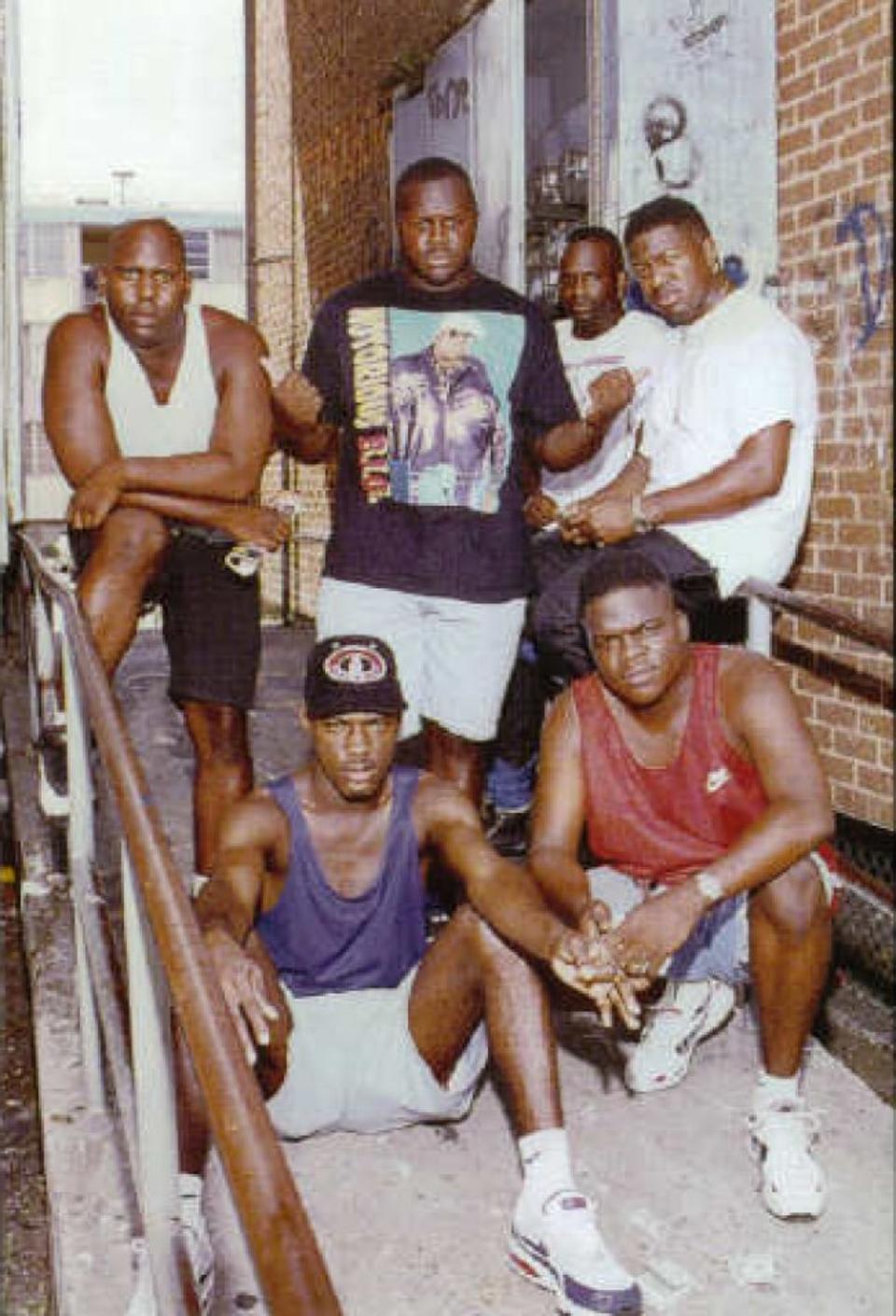

Acting as both the head of a record label, whose interest is in having the label make money, and as an artist’s manager, where your job is to fight for the artist, sets up an obvious conflict of interest. Lil Ya, who put out four albums on Cash Money as a part of the influential trio U.N.L.V. (they put out the original version of “Go D.J.,” just as a small example), said that Birdman didn’t give his group the choice of finding an outside manager.

“He didn't allow us to have our own manager,” Ya tells me when I call him. The rapper has lived in Houston since he left New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina. “He was like, ‘If you're part of this company, I gotta manage y'all.’”

Baby would use his dual role to negotiate appearance fees for his label’s artists, and then not inform the performers about how much money they were making. Then he would take most or all of the money for himself and his label, leaving the performers with almost nothing.

“We found out he was booking us for fees that we wasn't really getting,” Ya remembers. “We found that out from owners of clubs and stuff. We'd end up talking to the owner, and they'd let us know what they paid Baby for us. Come to find out, it was something totally different from what we got. We would get a show for like $2,000 and we'd only receive, like, $600 [to split] amongst us three.”

Ya says that Birdman pulled similar stunts with “everybody” on the label at the time. “We never saw a contract, and the other artists never saw one neither,” he explains. Slim confirmed that “we wasn't getting the money that we was supposed to get for shows.”

On top of the issues around live shows, payments for albums were another issue for the artists who made Cash Money into a regional powerhouse. Lil Slim remembers taking albums to the distributor “ten or twenty thousand” at a time. Ya confirms that U.N.L.V. sold around 65,000 copies of its debut album 6th & Barrone, and were moving more than three times amount that by the time of their final release for Cash Money, 1996’s Uptown 4 Life.

But when it came time to get paid, the artists heard nothing but stonewalling and excuses. Lil Slim says he didn’t get paid for any of the records he released, while U.N.L.V. was so underpaid that they actually sued for—and received—the rights to their back catalog.

By 1997, things had grown so bad that artists started leaving the label in droves. The idea that Cash Money, in Lil Ya’s words, “wasn’t paying us correctly” had begun to spread.

The Williams brothers, when asked about this, have consistently turned the blame back to the artists. “They were getting into drugs, smoking weed, and it was taking away from them handling their business,” Ronald Williams told author Terri Dougherty in a typical statement. “I was like, man, I can’t deal with this. So I just woke up one morning and told my brother, ‘You know what, I got to get rid of everybody here and start from scratch.’”

Lil Ya calls the talk of drugs and irresponsibility an excuse.

“The drugs wasn't the problem. They put it like that once they got the deal,” he says now. “It hurts me inside, how he [Birdman] just deliberately lied to try to sugarcoat his fault.”

Lil Slim is adamant on this point as well.

“They put books out saying that the first era of Cash Money artists was caught up in drugs and all that stuff, but it wasn't like that. They’re just saying that to cover theyself for what they did to us. It's wasn't like that. People might smoke a little green or whatever. But that hard stuff? Dudes wasn't dabbling in that.”

As if stolen gig money and non-payment of royalties wasn’t enough, Lil Slim has one more complaint: Cash Money stole his artist. There was a young rapper in Slim’s neighborhood who he brought to Baby with the understanding that Slim would be instrumental in signing the kid and presenting him to the world. That youngster was Lil Wayne. But right around that time, Slim left the label, and he could no longer get in touch with his would-be protégé.

“When I brought Wayne to meet Baby, it was to my understanding that Wayne was gonna be working under me, because I was already an established artist,” he tells me. “It was only right that it should have been like that. But they went behind my back and started doing it with him without me knowing about it, and I had left Cash Money. So it was all done behind my back, and I never had a chance to talk to Wayne about it.”

Years later, when Wayne had his own issues with Birdman, Slim, who is working on a book about his Cash Money years called Lil Slim: Cash Money Outlaw, was saddened but not surprised.

“It just was like a retell of what happened to me,” he says sadly about the newest stories of Birdman’s malfeasance. “Everything that's coming out [Wayne’s] mouth, what he told them happened to him, it all happened to me. And it happened to me first, before anybody. It just made me feel like, it's almost 20 years later, and he's doing the same thing.”

Lil Ya, who last saw Birdman and his brother during the festivities around Super Bowl XXXVIII (“We was selling our CDs hand to hand, workin', and they bought a few from us”), had sympathy for Weezy on hearing reports of the eight-figure lawsuit.

“I felt bad for him, because he was so young. He was real, real young when money started coming in. He was too young. So I couldn't fault him. But I did kind of fault Juvenile, B.G., and Mannie Fresh, because we gave 'em the heads up a long time ago. We told 'em, ‘The dude ain't right, man.’”

“I guess they just had to see for themselves.”